With nearly

90 described species, Aphonopelma, Pocock, 1897, is a huge and wide ranging genus throughout North America and parts of Southern America, central America and Mexico.

Most are semi-desert or scrubland species and are terrestrial burrowers. Most will survive quite happily in captivity without a burrow but a retreat should be provided nevertheless. A typical

terrestrial set-up is ideal consisting of a few inches of substrate (kept more on the dry side for this genus, especially the North American species where 60% humidity is adequate), a cork bark /

flowerpot hide and an open water dish. See here for more information

on housing. All species posses urticating hair and most are slow growing, taking several years to reach maturity. They are long lived (reports of 30+ years aren't uncommon) and they have been known

to fast for long periods between moults. Most are rather skittish in captivity but will only occasionally use urticating hair as defence and some can be very particular in their feeding habits. The

usual invertebrate prey is ideal supplemented with the occasional defrosted pinkie mouse of piece of raw, lean meat.

Common species in captivity:

Aphonopelma sp. 'Carlsbad green' (USA)

A robust, medium-sized burrowing species from the Carlsbad area of New Mexico. A hardy species that is generally brown in appearance with a slight green tinge to the carapace and femora. Can be

defensive at times when disturbed.

A. anax - (Chamberlin, 1940) (USA)

Commonly called the Texas tan, A. anax is a popular species in the USA and in their natural habitat they are opportunistic burrowers. This means they will construct their burrow wherever there is a

suitable site (under rocks, in abandoned rodent burrows and even in domestic surroundings such as lawns).

A. bicoloratum - Struchen, Brändle &

Schmidt, 1996 (Mexico)

One of the more colourful species in the genus, A. bicoloratum makes a welcome addition to any collection. A small to medium sized species from Mexico, it adapts well to captivity but like all

other Aphonopelma spp., it can be slow growing. Quite calm in captivity it rarely kicks urticating hair and will accept crickets at approx. monthly intervals once adult. A good display spider as

it rarely burrows but the substrate should remain on the drier side with a water dish available at all times. Sub-adult and adult males are quite different in appearance from females, the males

having a much darker carapace and legs. Once mature the males are overall dark brown to black. Spiderlings are sometimes available but in recent years wild caught adults have

appeared.

A. chalcodes - Chamberlin, 1940

(USA)

From the deserts of Arizona and Mexico, A. chalcodes is covered with light brown and reddish hairs that give its common name of desert blonde. Rarely burrowing in captivity and long lived, it

can fast for long periods in between moults (some account over 3 years!). An attractive species but captive bred spiderlings are rarely available and because of their slow growth rate, people prefer

to buy wild caught adults.

A. hentzi - (Girard, 1852) (USA)

Another popular species in the USA and sometimes called the Texas brown. Care in captivity is similar to other Aphonopelma spp.

A. moderatum - (Chamberlin & Ivie,

1939) (USA)

Another attractive species but highly variable in its colour. Care is similar to other members of the genus as are growth rates and fasting periods. Often called the Rio Grande gold it is covered

with golden hairs and some individuals have darker hairs on the patella making them particularly attractive.

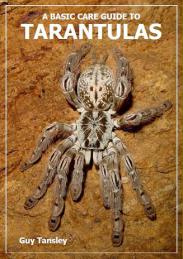

A. seemanni - (F. O. P.-Cambridge, 1897)

(Central America)

With it's very dark grey to black background coloration and striking white stripes down the length of the legs, A. seemanni is one of the most striking species available. There are many regional

and colour variations for sale labelled as A. seemanni but specimens with wide, white/cream leg markings are the original. All other less impressive specimens could either be colour variations or new

un-described species, only time will tell. Care should be taken not to accidentally cross breed these variants as the original colour form may be lost. It becomes obvious once the males mature as

they're quite different from the original specimens seen in collections around 15 years ago. My advice is to try and verify the identity of your spider before trying to breed it. Freshly moulted

spiders are vivid in their contrasting colours but this tends to fade throughout the moulting year. It adapts well to captivity (a good beginners species) but is slightly nervous and for this reason,

shouldn't be handled. They can be difficult to mate as the male is nervous (males possess tibial spurs) but with a receptive female, all should be straight forward. Eggsacs typically contain

several hundred spiderlings that grow relatively fast depending on food supply and temperature etc. There are many species of tarantula that have white 'zebra' leg markings

but A. seemanni certainly has the best. A must in any collection!